It’s every festival goer’s worst nightmare. You’re standing in a field, surrounded by an endless sea of bodies. The music is blaring, and as the energy builds the people press in, closer and closer until you’re unable to move, arms pinned at your sides, legs precariously balanced as you try to stay upright amidst the growing pressure.

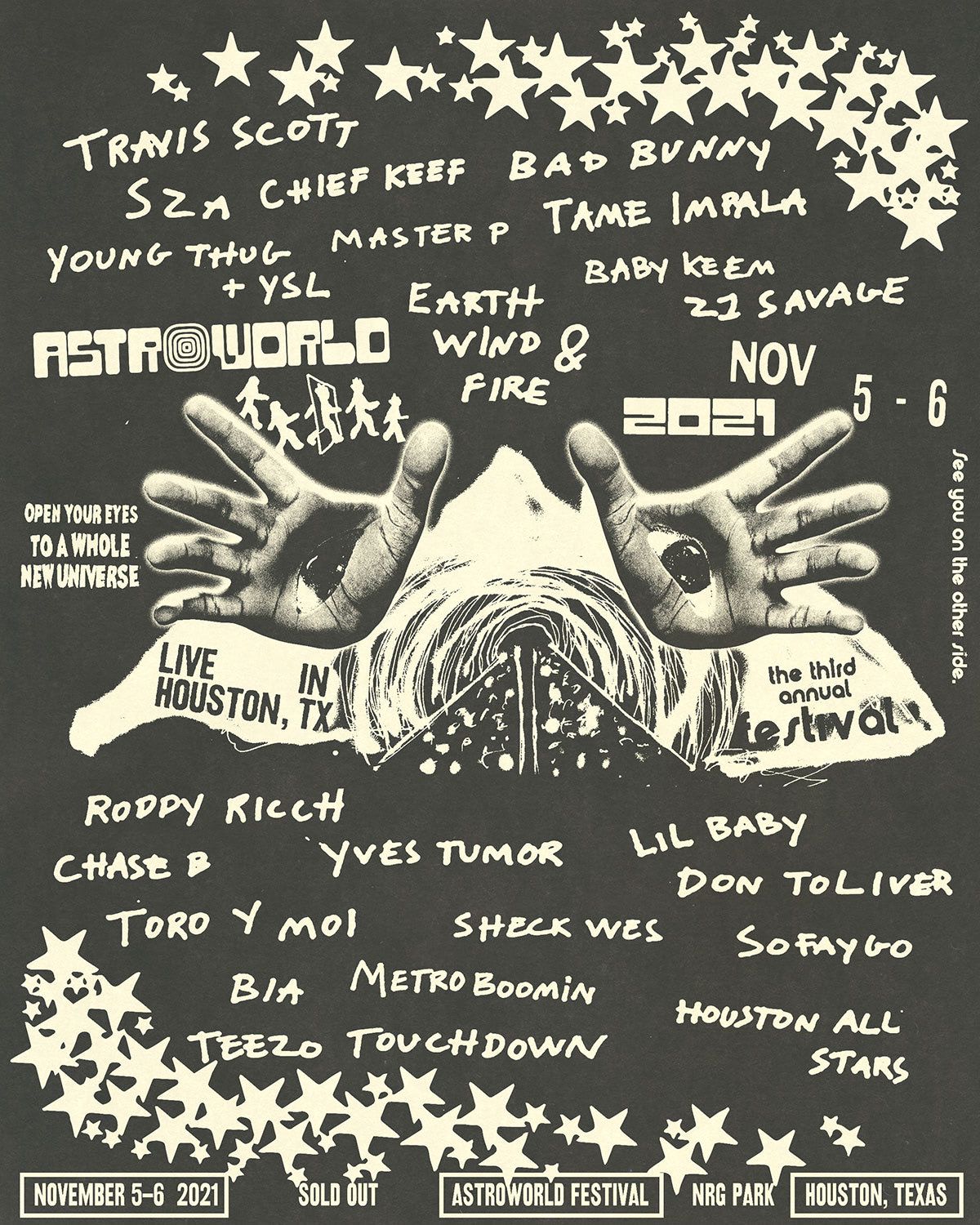

This is what it felt like standing in the crowd during Travis Scott’s set at Astroworld Festival in Houston Friday evening. The sold-out event was attended by over 50,000 eager fans at Houston’s NRG Park, eight of whom would never make it out of that deadly crowd. As soon as Scott posted the time he’d step onto the stage on the large monitors, attendees began pushing towards the front of the crowd, squeezing rows of people tighter as the mass of people churned. Almost as soon as he took the mic, the surge grew stronger, pushing fans against the barricade and into one another, until their ribs had no room to expand, suffocating them in place. This suffocation is referred to as compressive asphyxia. Footage and attendee statements describe people falling to the ground, overcome by the suffocation and physical exertion of the crowd. The surge was too strong, and fans watched in horror as these people were trampled right before their eyes.

All while this was happening, some attendees called out in desperation to crew members, begging them to stop the show. Videos show their pleas met with apathy and confusion, with damning footage emerging of Scott himself staring down at the lifeless bodies being carried out as he continues to hype up the crowd. ICU nurse Madeline Eskins took to social media to describe her experience on that fateful night, writing, “I tried to jump up as much as I could to get air. I couldn’t breathe. I just felt it. I knew it was coming.” As some fans tried to get help from the crew, you can hear others in footage from the catastrophe mocking their pleas, dancing on emergency vehicles, and continuing to push and push.

When I woke up Saturday morning to these shocking headlines, I felt a wave of bitterness wash over me. Since local and state restrictions have been eased, I’ve been lucky enough to attend a couple festivals and shows, eager to return to my pre-pandemic joy of live music. While none of these events resulted in the number of mass casualties we saw at Astroworld, I felt a distinct shift in my festival going experience. The crowd felt more hostile, more agitated as people moved in, and I left nearly every set or show I went to early, blaming pandemic anxiety for my discomfort. But I’ve had this nagging question in my head since returning to these events; was it really always like this?

It’s been a tough year and a half for artists and live event organizers alike. Festivals have become a billion-dollar industry, raking in millions of dollars after each three-day event, and in the age of streaming, touring has become the only viable money-making venture for artists. With all those revenues lost for over a year, event organizers and artists are desperate to revive the live music experience. This can lead to overselling tickets, maximizing venue capacities, and a lack of necessary festival infrastructure, which can be a deadly combination.

As music lovers, many of us also feel desperate to connect with our favorite artists live on stage once again. After a year of limited social interaction, we yearn for the days of losing ourselves in the ecstasy of a festival crowd. While vaccinations have greatly reduced the spread of COVID, preparing us medically for a return to normalcy, I wonder if we are psychologically ready to return. In the olden days, or at least pre-pandemic, we went into music festivals with largely reasonable expectations: those who wait are rewarded with better views, some A-holes might push past you, you might not get the best view of the stage amidst thousands of other GA attendees, and it’s more fun when you try not to piss off those around you. After nearly two years without large scale social contact, we feel hungry and deprived, wanting so desperately to make up for the lost time. At each festival I’ve been to, I’ve sensed this tension, as if we’re all lining up for our ration of fun at the end of a long cold winter. The crowds are more aggressive, anxiety permeates the festival grounds. Could the Astroworld tragedy be the culmination of our shared psychological predicament as we reenter the world we once knew?

There has been much criticism thrown at festival organizers, crew members, and Travis Scott himself over the weekend. There are measures organizers could have taken to bolster safety infrastructure, and a lot of the responsibility for the tragedy definitely falls on their shoulders. But the apathetic responses from crew members and Scott on Friday night offer some other intriguing insights into our post-pandemic lives. As attendees begged a camera operator to send for help, we can see his face, confused and unsure. This man was probably independently contracted by the festival, and his sole purpose is to capture every second of the performance. He doesn’t have the power to make the call to shut off the music, and so he is faced with a choice. He can either risk forfeiting his pay for the weekend or trying to help those in the crowd in any way he can, though amidst the chaos his actions may still be futile. When chaos erupts this quickly, we turn towards authority to protect us, and without a clear authority in sight, people defer their responsibility. It’s a classic case study in the Bystander Effect, really. What we forget when criticizing these crew members is that many of them have little power in this situation, they don’t know what to do and fear the economic consequences of crying wolf. Even Travis Scott himself was probably expecting “the man in charge” to step in if things got truly out of hand.

This isn’t the first time a mass crowd casualty event has occurred. The infamous Woodstock ’99 revival was a similar disaster, named “the day the music died,” with high temperatures and inadequate infrastructure agitating crowds until mass violence and enormous fires erupted. In 1989 at the Hillsborough soccer stadium in England, a crowd surge caused by a combination of inadequate space, crowd behavior, and flawed architecture killed over 100 fans. When two crowds collided at the 2015 hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia, over 2,400 people were killed. In the wake of each of these disasters, investigators were able to pinpoint strategies to curb the risk of deadly crowd surges and fatal events, including proper staff training, emergency response systems, responsible ticketing practices, and creating pathways for movement. Some responsibility also does fall on performers, who need to be conscious of the dynamics of a live show. I fell in love with live music because of its ability to sweep you up in the energy of the performance, but that alluring quality also makes these events dangerous. Travis Scott is known for imploring his audiences to “turn up”, creating a wild energy at his shows that initially put him on the map. With the combination of shoddy infrastructure, crowd psychology, and the nature of his set, it seems like a disaster like this was bound to happen. For the future of live music, we need to examine the causes of tragedies such as what happened at Astroworld, and consider whether it’s an individual’s fault, or the convergence of several collective forces. We can’t bear to have another “day the music died”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.